Whitespace Top 10

Museum, gallery or building dedicated to one artist

Dear Friends,

This month’s Top 10 is focused on museums, galleries and buildings dedicated to a single artist. I love dedicated spaces. Seeing a collection of work, sometimes a collection of madness, allows me to know an artist’s influences, inspirations, spaces and places and connect to their work at a deeper level.

This blog is a dedication to the artists, architects, thinkers and humans who inspire me and the galleries and museums that passionately dedicate space to these revolutionaries.

Love,

Susan

1. Cy Twombly Gallery Houston, Texas

Twombly Gallery, exterior | Courtesy of Culture Map

Here and Elsewhere by Cy Twombly, interior | Courtesy of schedios.tumblr.com

The Cy Twombly Gallery in Houston, TX is my a favorite gallery in the world; therefore, it is absolutely my favorite gallery dedicated to a single artist.

Cy Twombly sketched the initial design of the gallery, and Renzo Piano interpreted that sketch into a fully realized design to complement Twombly’s work. Twombly and Piano were a perfect team, and the gallery design reflects that perfect collaboration.

In the “everything’s bigger in Texas” city of Houston, the Cy Twombly gallery is unexpectedly quiet and understated. It is a perfect minimalist square set amongst large oak trees in a greenspace. The entrance to the museum does not even face the street but is placed directly in front of a particularly commanding oak tree. It’s as if the gallery is paying respect to the natural landscape and beauty that first claimed the space.

Inside, the gallery is approachable, natural and scaled to a level that allows me to experience and absorb the art without being overwhelmed by too much stuff. To me, the gallery is quiet and reverential.

And, then there’s the work. I love Twombly’s light and ethereal paintings. His drawings appear simplistic, but there is intentionality in every mark. Dare I say, the agency is undeniable? His layering of painting and drawing resonates with me on a purely emotional level. To me, the scribbles and scratches are a visual poem. This is my chapel.

2. The Rothko Chapel Houston, Texas

Rothko Chapel, exterior | Courtesy of Houston Museum District Association

Rothko Chapel, interior | Courtesy of Houston Museum District Association

Speaking of chapels, the Rothko Chapel is a quiet, meditative space dedicated to people of all religions and faiths. Like Twombly, Rothko had a hand in the design of the windowless brick building and worked with several architects, including Phillip Johnson, to complete the space. Let’s just say, the collaboration between Rothko and Johnson was a little less than perfect, but that’s a different blog for a different day.

The chapel’s interior displays Rothko’s massive black paintings that, according to Rothko, “…provide a physical depth that take the viewer into a glimpse of the infinite.” I like the space because it’s experiential. When I am in the Rothko, I am in the zone.

3. The Warhol Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

The Andy Warhol Museum, exterior | Courtesy of Expedia

The Andy Warhol Museum, interior | Courtesy of Flickr

The Warhol museum is the largest museum in North America dedicated to a single artist. Richard Gluckman designed the conversion of the building, which was originally a seven-story warehouse. The museum opened in 1994 approximately seven years after Warhol’s death.

When I think of Andy Warhol, I imagine him partying it up in Studio 54 in New York or hanging with all of his glamorous friends at The Factory. However, it’s important that his museum is located in the working-class town of Pittsburgh rather than New York. The location ties Warhol back to his humble beginnings as an immigrant coal miner’s son.

The museum reminds me that Warhol started out like the rest of us and that it’s up to us to seize our very own 15 minutes of fame.

4. Georgia O’Keeffe Santa Fe, New Mexico

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, exterior | Courtesy of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, interior | Courtesy of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

The Georgia O’Keeffe museum, located in Santa Fe, is in a renovated adobe-style home that was redesigned to house 3,000 pieces by O’Keeffe and her modern contemporaries. I love that the museum originated in a home…I wonder why? The setting allows me to imagine O’Keeffe painting in her own rooms at Ghost Ranch as she channeled the western light and dry calmness into her quiet, provocative work.

5. Frida Kahlo Museum Mexico City, Mexico

Frida Kahlo house, Casa Azul, exterior | Courtesy of So Sasha

Frida Kahlo house, Casa Azul, interior | Courtesy of All and Sundry Blog

Frida Kahlo, Casa Azul, is really a house museum and is as much a work of art as Kahlo’s paintings. Kahlo was born in the house in 1907 and lived there, off and on, her entire life. The walls are covered in her self-portraits as well as collections of memorabilia that contain documentation of a culture, time and place that spawned this amazing intellectual and bohemian artist. It’s mind-blowing to see the tiny bed where she lay her head and painted after her accident.

I have a deep fascination and connection to Kahlo. I don’t know if it is her love of home, her willingness to invite people into her home or her ability to keep working and fighting despite her disabilities. Maybe it was her ability to rock those eyebrows?

6. The Picasso Museum Barcelona, Spain

Picasso Museum, Barcelona, exterior and interior | Courtesy of Eric Vokel

Picasso Museum, Barcelona, interior | Courtesy of barcelona.cat

The Picasso is a museum set in a medieval mansion. This was the first museum dedicated to Picasso’s work and the only one created during the artist’s life. It’s amazing to see the comprehensive representation of Picasso’s early work, which is rooted in classicism. It’s here that I saw Picasso’s very first explorations into modernism and cubism.

I first visited this museum when I visited my daughter, Caroline, who was studying in Barcelona. Together, we wandered the twisting medieval streets and explored the Gaudi sites in the very ordered Eixample. The push and pull of the old and new and the rebellion against the strict grid crystalized the impact that place had on Picasso’s work.

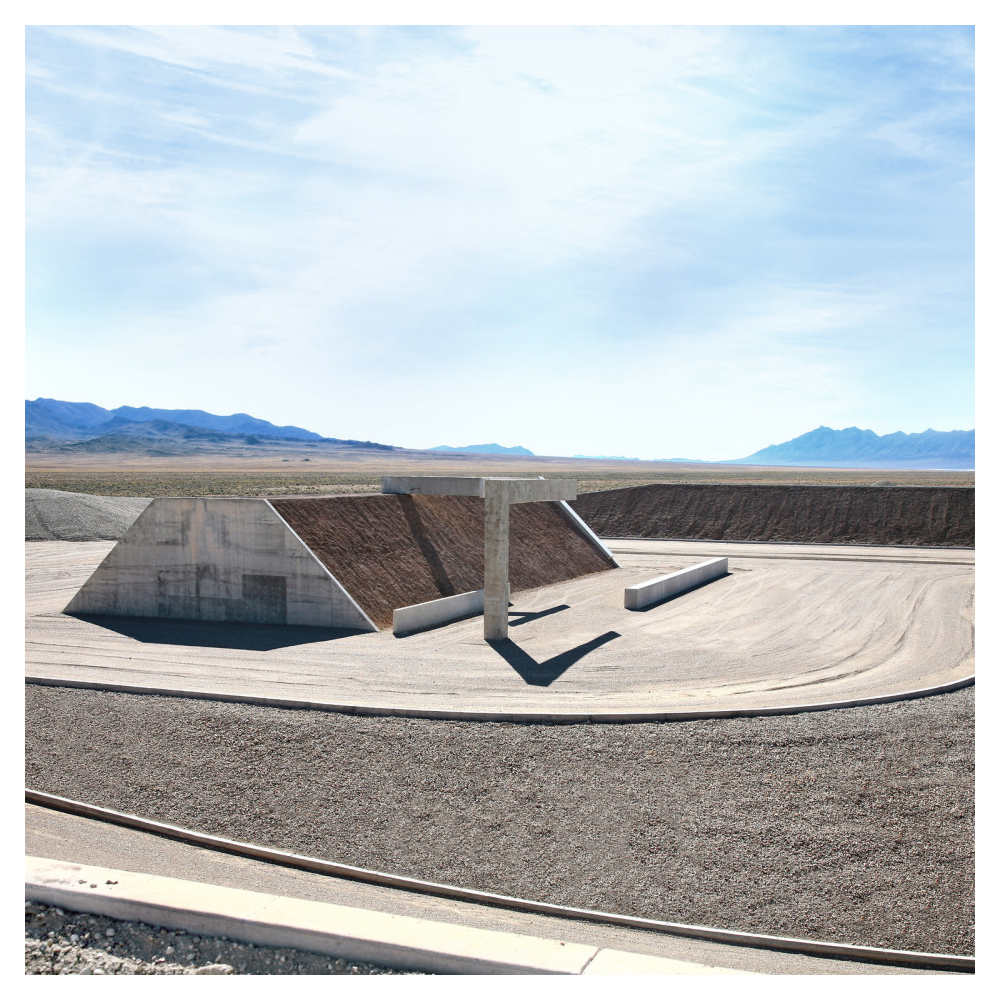

7. James Turrell Museum Colome, Argentina

James Turrell Museum, Argentina, exterior | Courtesy of Vaya Adventures

James Turrell Museum, Argentina, interior | Courtesy of NY Times

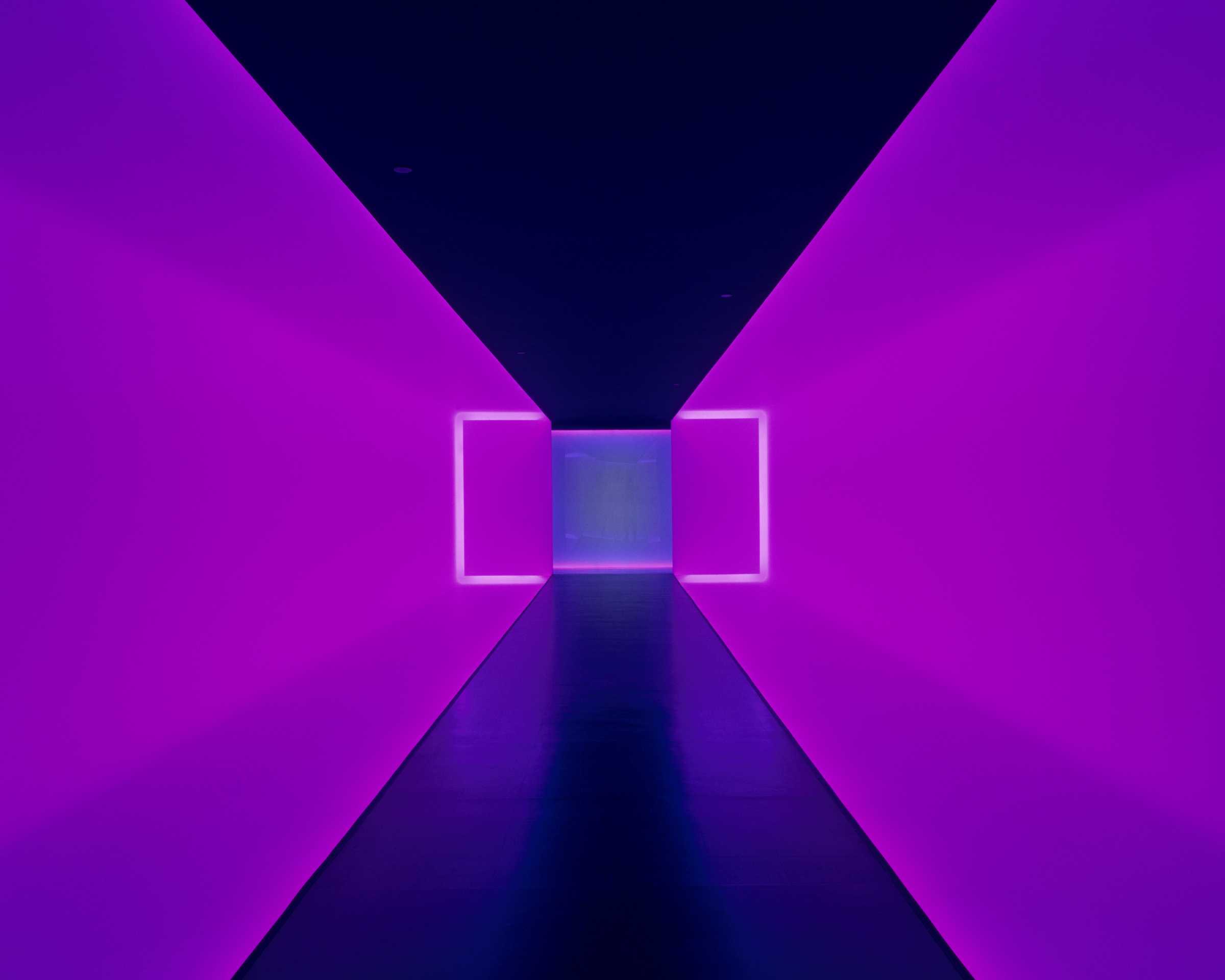

James Turrell Museum, Argentina, interior | Courtesy of Hiram Butler Gallery

This museum lives in a vineyard in a remote area of Argentina. It is not a trek for the faint of heart. After two plane rides and a three-day drive through the Andes Mountains, I found the museum located in the Hess family’s vineyard.

Like the Cy Twombly Gallery, the museum is based on a plan created by the artist and showcases nine light installations and five decades of works on paper. This is the only museum in the world dedicated solely to the work of James Turrell. To me, Turrell’s work is quiet and transformative and connects me with the heavens…the vineyard’s wine also helps with that connection.

8. Tamayo Mexico City, Mexico

Tamayo Museum, Mexico City, exterior | Courtesy of Arch Daily

Tamayo Museum, Mexico City, interior | Courtesy of Arch Daily

Rufino Tamayo was born in Oaxaca, Mexico but lived in Paris and New York where he worked with graphite, paint, and ink. He was instrumental in building this museum, which is beautifully situated in a central park in the middle of Mexico City.

Tamayo’s paintings combine Mexican styles with Cubism and Surrealism. Tamayo was influenced by his Zapotec heritage, and the structure itself reflects the colors of the Mexican landscape much like the ruins near Oaxaca.

Mexico is a place I return to time and time again. I love Mexico City for the museums, high energy population, vibrant colors, architecture, murals, public art, amazing food, and the many varieties of mezcal to be enjoyed. What else could you possibly want in a travel destination?

9. Sir John Soane’s Museum London, England

Sir John Soane, London, exterior | Courtesy of KudaGo

Sir John Soane, London, interior | Courtesy of KudaGo

This is my list, so I get to pick the artists, and I consider Sir John Soane one of them. Soane made his name in England as a neoclassical architect and designed many buildings in the city, including the Bank of England. His house museum was largely untouched when it opened to the public in 1837.

For me, the most interesting aspect of the house is the filtered light that moves from floor to floor flowing down from the clerestories high above. This place is a brilliant combination of light and space.

Sir John was a collector of collections and, for those of you who have ever been in my cellar, you can probably see the resemblance between his home and mine; although, his collection contains Greek and Roman antiquities and mine is a curated selection of ball jars and tote bags. After visiting his museum, I was inspired to paint my living room, floor to ceiling, blood red.

10. Van Gough Museum Amsterdam, Netherlands

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, exterior | Courtesy of Arch Daily

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, interior | Courtesy of Babylon City Tours

The Van Gough Museum is located in a building designed by Gerrit Rietveld and Kisho Kurokawa. The museum hosts the largest collection of Vincent Van Gogh’s paintings and drawings in the world.

Moving through the museum, the floors get narrower and narrower as one ascends. There is an urge to panic, but the beautiful natural light from the glass ceiling and the clean lines of the structure provide an atmosphere of quiet consideration, something necessary when viewing a collection of this intensity and magnitude.

Because Rietveld didn’t ascribe to the architectural and intellectual snobbery of the day, fellow architects looked down on him. However, I’m certain he knew what he was doing. It inspires me to see creators who keep creating even when they are disparaged and criticized by others. He focused on the art and design and let the criticism fall away.

11. Dali Museum Girona, Spain

Dali Museum, Barcelona, exterior | Courtesy of Into the Blue blog

Dali Museum, interior | Courtesy of wanderful-world.com

I have not yet visited this museum, but it’s on the list. The exterior roof is lined with statues of Napoleons wearing French bread bicorn hats. Need I say more?

Although we don’t have a museum in Atlanta dedicated to a single artist, Michael Rooks at the High has done a magnificent job of creating a powerful collection of contemporary art, and we are very fortunate to have him.

In addition, we have some great house museums like the Wren’s Nest and the Swan House that let us peek into a specific era. And, you are always welcome to enjoy whitespace and the wonderful artists who make the gallery their artistic, and sometimes temporary, homes.

Get out there and explore what Atlanta has to offer! Start by visiting the High Museum, Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, Spelman College Museum, MOCA GA, The Carlos, and The Zuckerman. And remember one of the best things about living in Atlanta is that we have a great airport, adventure is only a plane ride away.