There was a fantastic turnout for Dr. Jerry Cullum’s curator talk at whitespace on Thursday. Over 50 visitors spanning the worlds of art, science and everything in-between braved the torrential downpour for his presentation on From Cosmology to Neurology and Back Again. With his signature mix of scholarly analysis and humor, Jerry took us on a journey discussing the interconnections of the show. Starting with Karley Sullivan’s 160 Moons and continuing on a thematic journey through the other works in the gallery and adjoining spaces, Jerry explained their placement in the show and shared thoughtful anecdotes for each work. Continue reading

Just Asking. (More Issues Only Partly Addressed in the Curator’s Talk) by Jerry Cullum

My sense is that everything Freud and Jung believed and perceived is true, but true as viewed through two sets of incompatible distorting filters inherited from segments of nineteenth-century European culture, a factor that neither of them took sufficiently into account. (Both men felt that further biological research would eventually bear out their largely intuitive findings.)

Likewise the perceptions and speculations of neurology are true, but are viewed through yet another set of distorting cultural filters. We believe these cultural filters are the very structure of reality itself, because we live inside them and can’t see them until we learn to see them—and maybe not even then.

An interesting experiment reported in the Sunday, July 8 New York Times involved showing doctors sets of data on patients, with some of them shown a photograph of the patient as white, and others shown the same patient as black. The course of treatment the doctors prescribed turned out to be tinged by racial presuppositions even though the doctors believed they had no racial biases.

The key to the experiment is that the doctors who realized that this was probably a test about racial attitudes prescribed courses of treatment that showed no deviation according to race. (It would be interesting to see if the same results would obtain for gender, socioeconomic status, physical attractiveness, and other variables, but given the number of doctors who read the New York Times and the journal in which the results of the experiment were published, the possibility of conducting these further experiments has pretty well been eliminated.)

The conclusion of the experimenters, and it may be an overly simple one, was that a moment of self-aware reflection could correct for unconscious presuppositions that influence seemingly unrelated decision-making. This is a way of overcoming the tendency to jump to conclusions that has been hard-wired into us by—evolution? By something or other, anyway. We might stop for a moment and think about how we construct probable models, and why we build them the way we do….

To what extent do we have to take account of how we are hard-wired, and how our ways of sitting over coffee or just-sitting-when-sitting might influence the outcomes of our inferences, whether we are drawing conclusions about particle physics or macroeconomic theory or art exhibitions? Can we really rely exclusively on “rational” methods to filter out or correct for responses that are almost entirely not under our conscious control because they are not even part of our conscious awareness, much less our control?

Just asking.

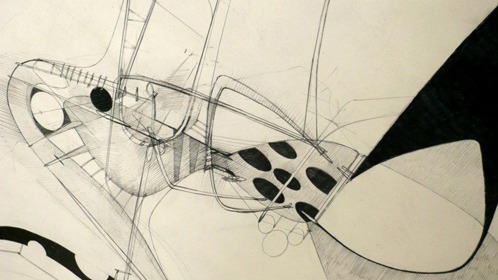

Dr. Jerry Cullum explains his thinking behind the look and feel of the “From Cosmology to Neurology and Back Again” exhibition at whitespace

“From Cosmology to Neurology and Back Again” explores why human beings are so seldom able to comprehend the full dimensions of complex systems—systems from cosmology to chemical evolution, to the politics of ethnic difference, to the consequences for the world’s waters of everything from contemporary mining practices to large-scale climate change; we not only do not understand such systems, we are unconscious of the effects of our newest technologies on how we perceive and think, and thus this also is a subject explored by the exhibition.

Neurology and the cognitive sciences have given us insight into the biology of barriers to comprehension, but the biology has to be understood in the context of individual psychology and the impact of our culture on that psychology. This is in itself a complex system that has its own set of barriers to understanding.

Rather than being didactic, the exhibition works by indirection on the viewer’s unconscious perceptions, aiming to make an impact through intriguing, seductively lush visual imagery meant to lead the viewer to learn more.

For more thoughts on this exhibition, check out the Creative Loafing article by Grace Thornton. “From Cosmology to Neurology and Back Again” runs through August 4th with a curator conversation on August 2nd at whitespace.

Sally Heller inspires Pre-K students at GSVA

Whitespace artist, Sally Heller, has been an inspiration to the Pre-K Young Explorers class at Granville Studio of Visual Arts in Ohio. GSVA is a non-profit organization collaborating with top artists and designers in building minds and cultivating innovation by bringing breakthrough creative education experiences to Central Ohio serving students of all ages from preschoolers to senior citizens. Rachael Moore, who assisted Sally in building an installation in Ohio, is GSVA’s Arts Integration Project Coordinator. Rachael had her pre-schoolers, the GSVA Young Explorers, construct an installation made with new and recycled materials to create “a contemporary forest of sorts” much like the artificial landscapes Heller is known for. This project is part of the series theme “From the Ground Up” in which the students create “experimental, temporary artworks in nature [including a vegetable and herb garden!] then persevered them through photography produced with digital SLR cameras.” The show will be on display through August at the GSVA Eddie Wolfe Gallery.

Below is an excerpt written by Rachael to Sally Heller explaining how the students were inspired by her work:

“On the last day of class (they come for 2 hours once a week for 9 weeks), the preschoolers were asked if they remembered the name of the lady who our art is inspired by and a 4 year old was impressively quick to call out your first and last name, in which started a “Sally Heller” chant where 12 preschoolers screamed your name at the top of their lungs repetitively for like 7 minutes straight inside the GSVA Eddie Wolfe Gallery where we were in process of installing the show together. It was crazy out of control, wish you could have been there to experience it.”

“The story is trying to tell the story”—still more explanations from Jerry Cullum

The vast majority of the flood of books about what Eric Kandel calls “a new science of mind” (a science which he defines as the confluence of brain science and cognitive psychology) are based on the writers’ previously held positions in debates that are at least a century old, and in some cases two or three or four centuries old. (Heck, some of the positions date back to the pre-Socratics of very ancient Greece.)

This is what we would expect, of course, and it’s why it’s important to keep the influence of culture in mind when we are talking about mind in biological terms. But the book writers’ opinions also reflect their underlying emotional dispositions, especially when they are proudly declaring their rationality.

One way or another, when we talk about such matters, “The story is trying to tell the story,” as Beth Lilly’s photograph has it near the conclusion (or is it?) of “From Cosmology to Neurology and Back Again.” We are part of the story, even when the story is about such seemingly objective and non-human matters as cosmology, chemical evolution, or the behavior of the world’s waters from the Antarctic ice shelf’s icebergs to the Japanese tsunami to the Pennsylvania aquifer (which is—or is not?—being shaken by hydrofracking).

Fortunately, we can change our minds (or something can change our minds—let’s not leave the hard-core determinists out of the debate), whether or not we can change our personality. Our minds actually modify the structure of our brains, to some degree, as our culture and our personal experience reshape the paths and quantity of neurons. (See: “neuroplasticity,” which I grossly oversimplify almost to the point of misrepresentation.)

“From Cosmology to Neurology and Back Again” is my own effort at mind-changing, my own mind most of all.

I encountered some useful cultural and cognitive collisions on the first day of Barbara Maria Stafford’s Neuro Humanities Entanglement Conference back in the spring at Georgia Tech, and have encountered such collisions again (courtesy of Barbara Kaye’s gift of the book) in the past two weeks since the show opened: in Nobel-laureate neurologist Eric R. Kandel’s remarkable synthesis of science and art history, The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and the Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present. (The proliferation of long, descriptive subtitles is a side effect of how we first encounter books these days in new media and in bookstores, but that’s another story.)

I would say more right now about both the conference and the book, but I’m trying to move slowly towards the art of someday writing the haiku we call tweets…as the long-ago politician Hubert Humphrey said once when asked to deliver a twenty-minute speech, “The last time I spoke for twenty minutes is when I said hello to my mother.”

By the way, would the great aphorists from Martial to Oscar Wilde have loved Twitter, or what? It isn’t just for haiku poets. As Ezra Pound wrote, “Dichten=condensare.”

Wall texts: another curator’s comment on “From Cosmology to Neurology and Back Again”

still another note by Jerry Cullum on “From Cosmology to Neurology and Back Again”

I have always been a big fan of wall texts, even though I critiqued them in one of my early conceptual-art pieces for Lisa Tuttle’s “Oh, Those Four White Walls” show. (“Before You Proceed Further, Please Read This” was a wall text exploring the pitfalls of and preconceptions behind wall texts.) In fact, I have often told artists that if viewers need to be put in a particular frame of mind by knowing some information about the art, that information had better be someplace where they can’t miss it, like on the wall.

There wasn’t time or budget to do that with “From Cosmology to Neurology and Back Again,” so the show tries to provoke viewers into wanting to find out why they feel what they feel about it, regardless of whether they read the curator’s statement before looking at the art.

I tried to make viewers react to the show by wanting to go back through it again, or at least explore parts of it more than once. (All the juxtapositions are meant to elicit this reaction.) Some of the show’s visual metaphors and interconnections are too condensed to emerge into consciousness on first viewing, so there was a practical as well as conceptual reason for sending smartphone-wielding viewers in a complete circle by incorporating QR codes—Henry Detweiler’s concept and artwork, but my choice of QR codes—that lead to the webpage photographs on which Karley Sullivan’s drawings of moons of the solar system were based. (There was also the idea that some viewers still don’t carry smartphones, or wouldn’t perceive the framed artworks as real QR codes.)

On the purely conceptual level, this is an extremely abbreviated way of introducing the idea that our information technology interacts with our inbuilt mental habits to influence the way we respond to the world. Marcia Vaitsman’s image immediately adjacent to Henry Detweiler’s QR codes conveys the same notion, but it conveys it only if viewers know that it’s a picture of the Japanese tsunami constructed by piecing together successive video images. There is nothing self-evident about Vaitsman’s piece, any more than there is anything self-evident about Seana Reilly’s pieces incorporating information about fracking and, coincidentally, about the dynamics of tsunamis. (I knew Reilly’s works were very beautiful and they looked conceptually provocative, but I had no idea what the scientific allusions of the titles and internal elements of the pieces were until Reilly told me.)

“From Cosmology to Neurology and Back Again” is more like a systematic allusion to a complex set of ideas than an exploration of them. Each individual wall of the show is an independent visual argument that is meant to intrigue and entice rather than demonstrate and explain. As I have said about conceptual art, if you don’t like looking at it in the first place, you won’t want to stop long enough to discover what it’s all about.

But I still wonder whether I should have stuck a couple of words on the wall to get viewers in the mood.

Maybe a line at the beginning saying “This is not an exhibition about cosmology.” Then a line on the opposite wall saying “This is not an exhibition about neurology.” Then maybe in the next gallery, “This room is not about the politics and cultural meaning of water.” Then maybe by Beth Lilly’s photo, “And this is not an exhibition about exhibitions, either.”

I thought of a few more, but they would just be random punch lines without purpose. Though one that says “Please notice which walls don’t have any wall text” might be to the point.

Tommy Taylor shares his recent experience at Artestudio Ginestrelle

Whitespace artist, Tommy Taylor, guest blogs about his recent artist-in-residency experience at Artestudio Ginestrelle, which offers a residency program to literary, visual and performing artists worldwide and is located outside the beautiful town of Assisi in Italy.