Whitespace Top 10

Top 10 Favorites in 2017

The December Top 10 is a wrap up of the best things I saw in 2017! I hope you enjoy it!

Love, Susan

1. Atlanta Ballet – Carmina Burana, Cobb Energy Center, Marietta, GA

The choreography and music was the best, and the Georgia State University singers and master singers knocked it out of the park. This performance instilled a sense of pride in me for the city we live in and the great art and cultural institutions that make a difference in Atlanta. The performance was, quite simply, beautiful and seductive.

Rachel Van Buskirk and Jonah Hooper in “Carmina Burana.” | Courtesy of Charlie McCullers

2. The Dougs…

Doug Aitken – Mirage House, Palm Springs, CA

I’ve never seen anything like it…the mirrored (inside and out) single story ranch house was a perfect realistic, and unrealistic, object set in the foothills of the San Jacinto Mountains. It made me question everything. I’m still not quite sure what is real and what isn’t?

Doug Shipman – New CEO of the Woodruff Arts Center

He’s pounding the pavement, meeting and talking to everyone and taking the efforts Michael Rooks started a few years ago to a whole new level. The best thing about Doug is that he probably knows it all because he is really smart and has accomplished a lot on this planet and for this city, but he doesn’t act like he knows it all and he still listens.

Doug Jones – First Democratic Senator in Alabama in 25 years.

This election shows us that our votes do matter and change can happen anywhere.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aZglqkCRNt8

Artist Doug Aitken, Mirage House, Palm Springs, CA | Courtesy of Susan B.

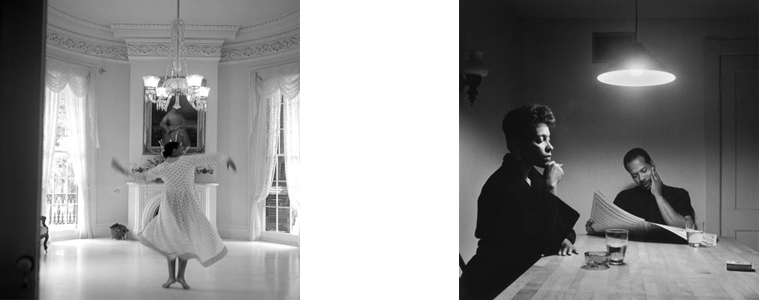

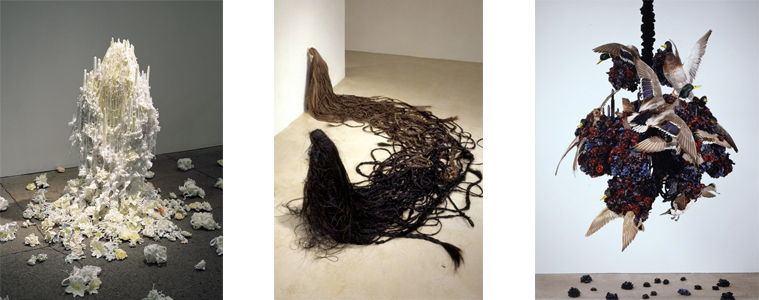

3. Nick Cave – Mass Moca, North Adams, MA, Closing performance of Until

This was the most moving contemporary arts performance I have ever seen. As Nick danced, he physically touched almost everyone in the audience. As he was doing so, he began to cry. The tears were for Michael Brown and the violence in Ferguson and all over this country. Nick’s tears were our tears.

Artist Nick Cave, Until, Mass Moca, North Adams, MA | Courtesy of Susan B.

Underneath the center of Nick Cave’s sculpture | Courtesy of Susan B.

Bob Faust and Nick Cave, Until, Mass Moca, North Adams, MA | Courtesy of Susan B.

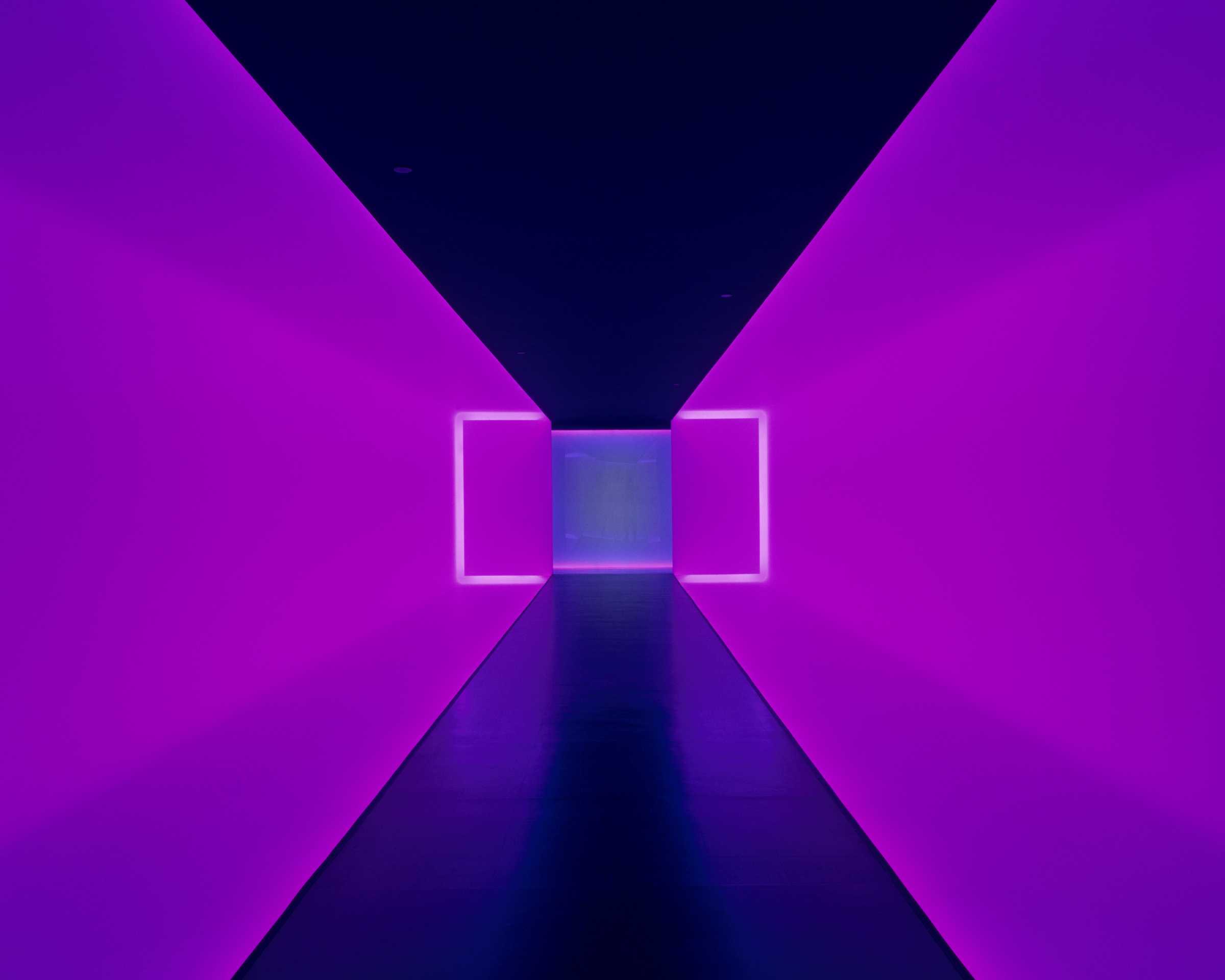

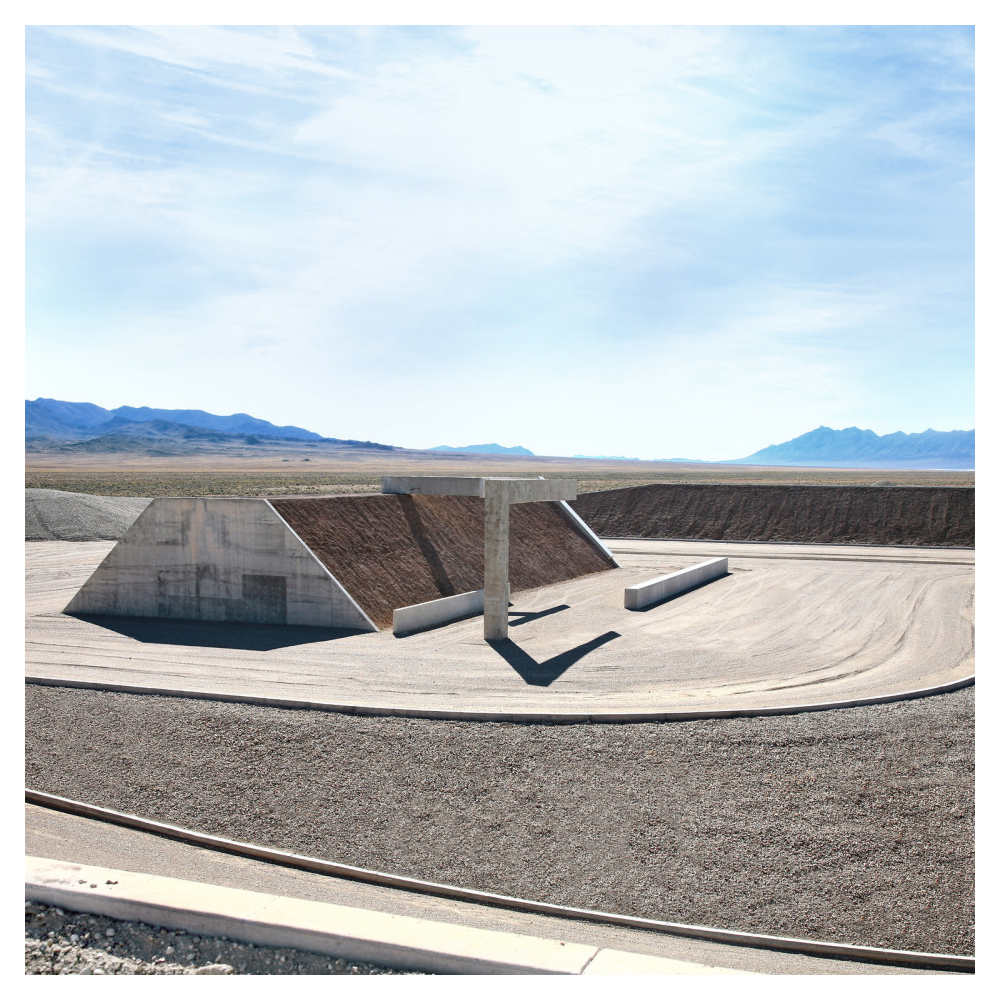

4. Robert Irwin – Chinati Foundation, Marfa, TX

Irwin has been working on this site-specific installation at Chinati for over 20 years, and it’s one of the best examples of the California-based light movement that started in the early ‘60’s. Irwin’s ability to traverse ultimate darkness into complete illumination using a simple scrim is indescribable. The installation is subtle, perfectly composed and completely immersive. I can’t label it – if I try, it dilutes the experience.

Robert Irwin, Exterior view of inståallation at Chianti, Marfa, TX | Courtesy of Susan B.

Robert Irwin, Exterior view at sunset (natural light filtered through scrims) | Courtesy of Susan B.

Robert Irwin, Interior view of installation at Chianti, Marfa, TX | Courtesy of Susan B.

5. The Eclipse – The Cumberland Plateau, August 21, 2017

Paul Thorn at the Song Bird, Days Inn, Trader Joe’s, Chani Nicholas, Seana Reilly, and homemade eclipse helmets. It took us from the ridiculous to the sublime and was beautiful and transformative. Who needs land art when you have solar art?

Paul Thorn’s airstream at the Song Bird, Chattanooga, TN | Courtesy of Susan B.

My precious daughter, Caroline, wearing a homemade eclipse helmet to view the Eclipse, Cumberland Plateau, TN | Courtesy of Susan B.

The Eclipse Cumberland Plateau, TN | Courtesy of Susan B.

6. Cover Books – Ephemera in shedspace, Atlanta, GA

What began as a temporary outpost for art books at whitespace is now a welcome addition to our ever-expanding whitespace environment at 814 Edgewood. We are so happy to have Katie because we are Cover Lovers.

Ephemera by Cover Books | Courtesy of Katie Barringer

Inside shedspace | Courtesy of Katie Barringer

Cover Books founder/owner, Katie Barringer

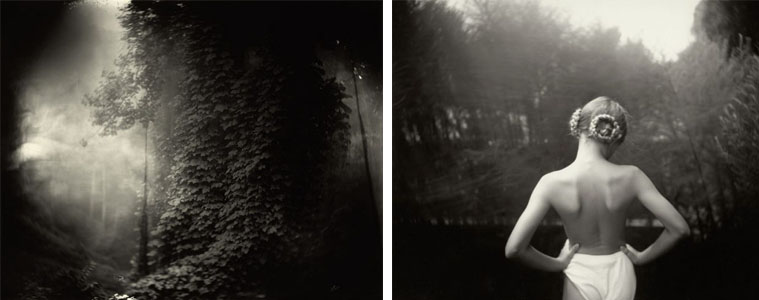

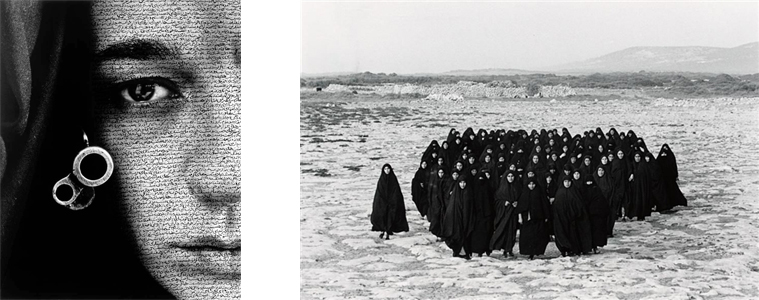

7. Kahlil Joseph – Wildcat at Prospect 4, New Orleans, LA

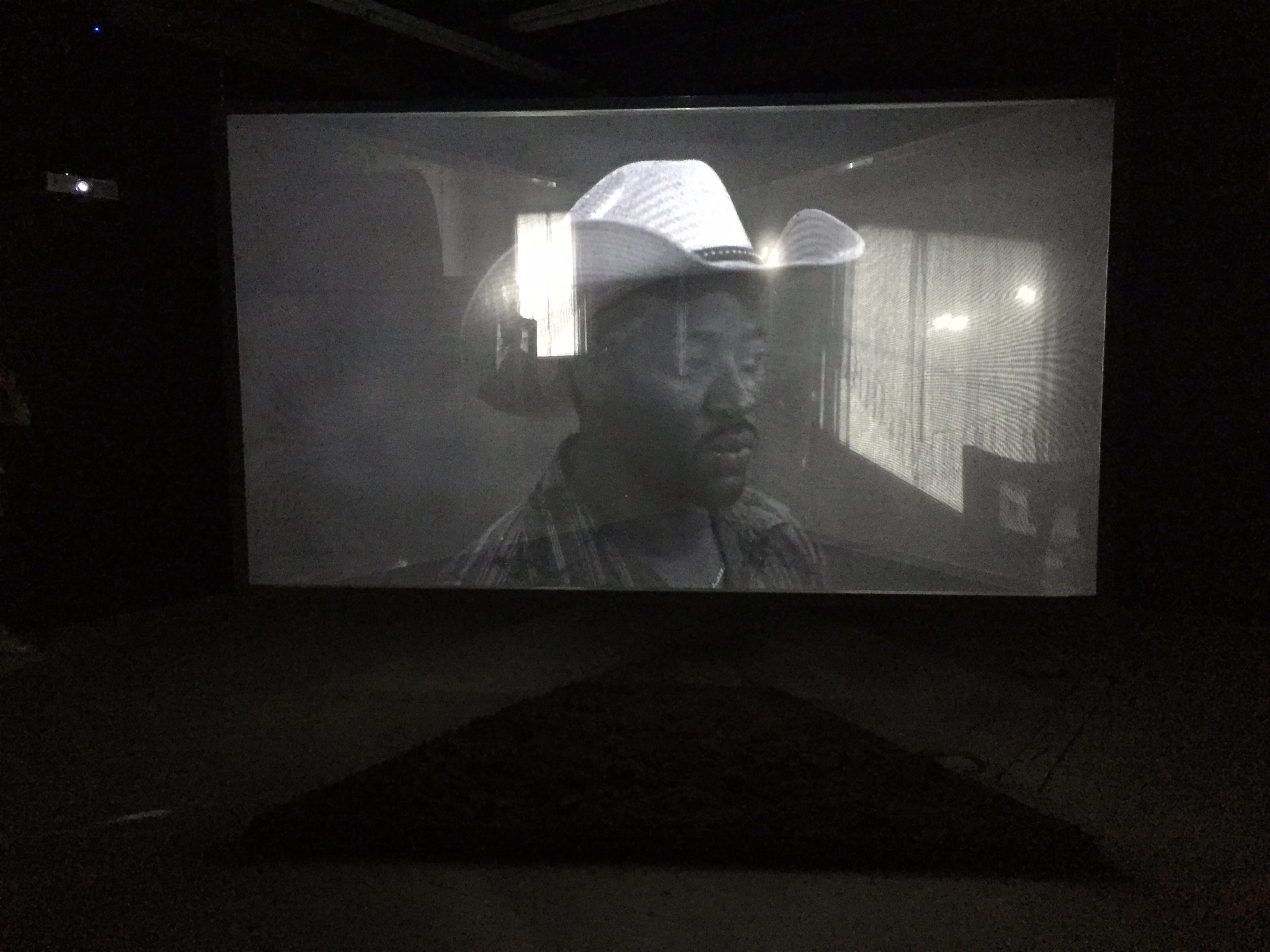

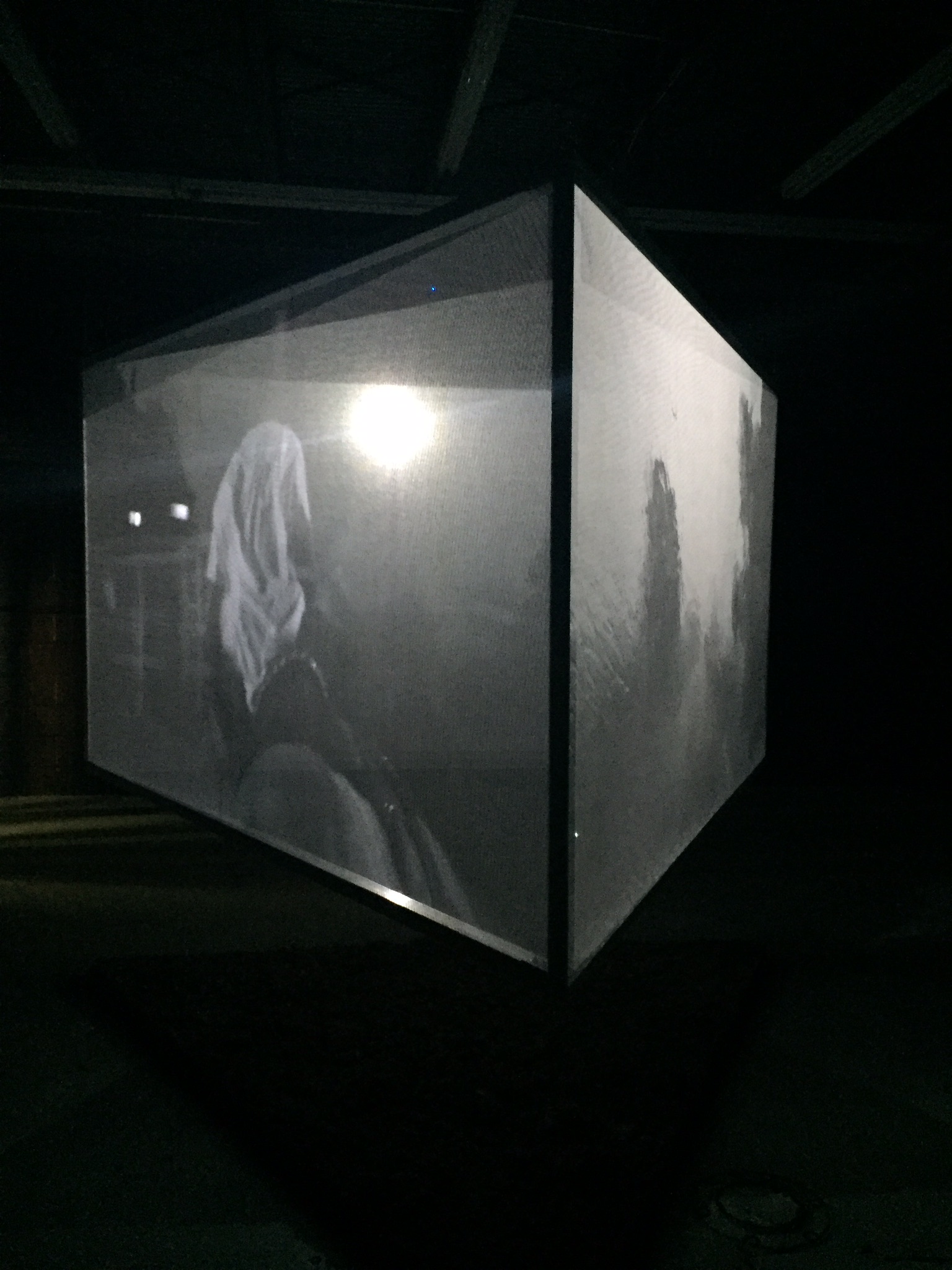

I almost overlooked at Prospect 4 this year but a definite fav was the poetic, narrative video, Wildcat. A black and white piece about the black rodeo subculture in the United States. It had all of the elements that intrigue me – it was dark and dangerous but beautiful both visually and musically. The sound by Flying Lotus is as important as the film.

Artist Kahlil Joseph, Wildcat, Prospect 4, New Orleans | Courtesy of Susan B.

Artist Kahlil Joseph, Wildcat, Prospect 4, New Orleans | Courtesy of Susan B.

Still from Wildcat | Courtesy of IndieWire

8. Yayoi Kusama – Festival of Life, David Zwirner NYC

Two concurrent, well actually three, shows at Zwirner proved that Kusama is an artist to be reckoned with and much more than an Instagrammer’s delight. The gallery adjoining the infinity rooms contained 66 double hung canvases that felt very much like works by southern folk artist, the late James Harold Jennings. These paintings were very colorful and filled with energy and playfulness. Mirrored balls, Christmas lights, and big red dots (you know how I love a red dot on anything) made standing outside on the sidewalk for two and a half hours on a snowy New York morning totally worth it. It was pure fun.

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirror Room, David Zwirner NYC | Courtesy of David Zwirner

Yayoi Kusama, David Zwirner NYC | Courtesy of Susan B.

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Net paintings and With All My Love For The Tulips, I Pray Forever, David Zwirner NYC | Courtesy of David Zwirner

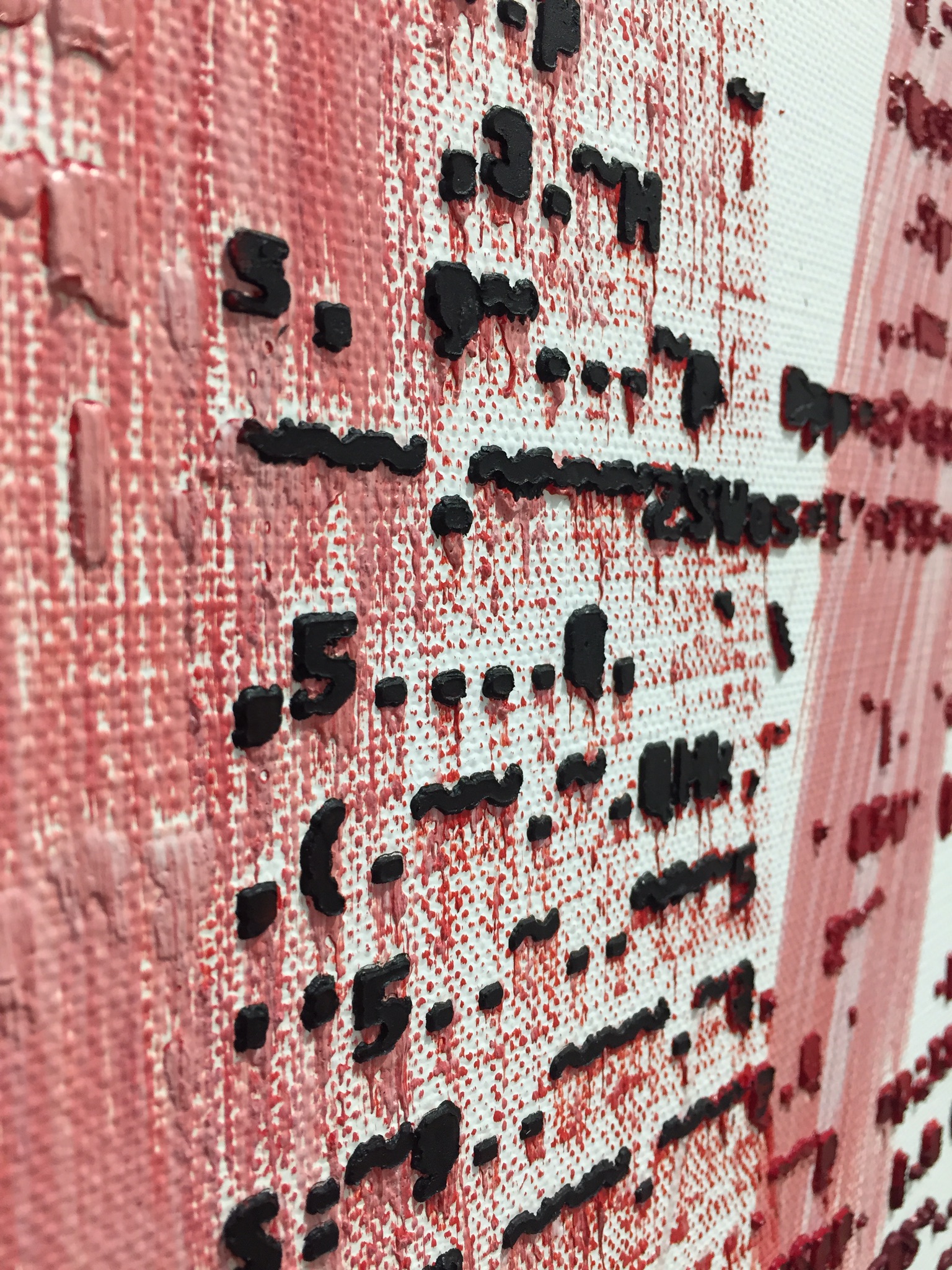

9. Jacqueline Humphries – Greene Naftali gallery, NYC

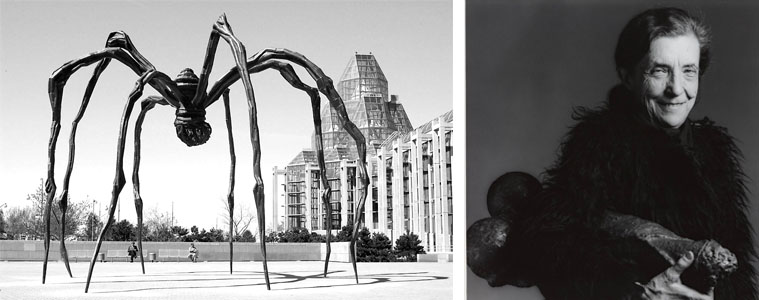

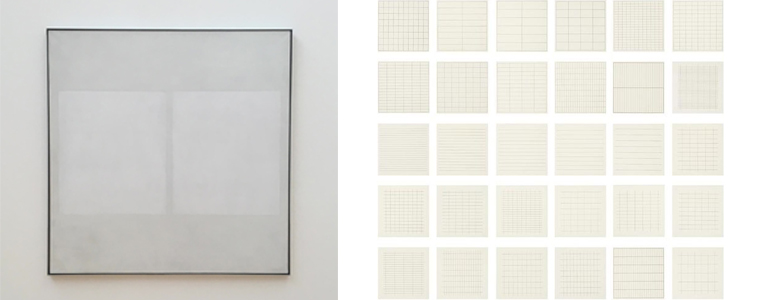

This show was quite a surprise and a good one at that. At a distance, her huge paintings could pass for an Agnes Martin/Cy Twombly mashup, but after close observation, Humphries’ are very much au currant. Her surfaces are layered with tight grids of cut out emoticons. What is she trying to tell us? Whatever it is, there is a lot of content, and much to think about in this work.

Jaqueline Humphries, (L) (#J^^), 2017, 100” X 111”, Oil on linen | Courtesy of Susan B.

Jaqueline Humphries, TQ555, 2017, 100” X 111”, Oil on Linen | Courtesy of Susan B.

Jaqueline Humphries, TQ555, 2017 | Courtesy of Susan B.

10. Mexico City, Mexico

I love everything about Mexico City. The museums, the architecture, the parks, the gardens, the food and, of course, the lovely Mezcal cocktails.

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

Courtesy of Susan B.